Christopher Hurrion has been interested in carriage clocks since being given a broken one nearly forty years ago. This he cleaned and set going again; in his own words more by luck than through technical knowledge. Having been seduced by the love of horology nearly 40 years ago, he and Charles started a joint enterprise on Paul Garnier. He has built on those foundations since then. As a result far more is now known about him and his carriage clocks, especially the sequence in which most of his models appeared, than when Charles’ and Peter Bonnert’s seminal book ‘Carriage Clocks’ was published.

Jean Paul Garnier (1801-1869), known simply as Paul Garnier, was most properly given full credit by the mid-19th century French Horological Establishment for being the creator of the Parisian carriage clock industry. In this connection Christopher paid tribute to E. Flachat, the writer of P.G’s obituary, which appeared in the Revue Chronométrique of 1869. It is to Flachat that is owed most for our knowledge about Garnier’s early life, his career, his business and interests generally. P.G. of course, was not the first in France to make carriage clocks; that credit almost certainly belongs to Breguet, more than 30 years earlier. What, however, P.G. did do for the French carriage clock was to make their products affordable to ordinary people when they had previously been beyond their means. Paul Garnier’s more or less factory-made carriage clocks left nothing to be desired while remaining comparatively inexpensive. The proof of their excellence is how many early examples, some of them over 180 years old, go today as briskly and reliably as when they were first made. Their sheer quality needs to be closely analysed to be appreciated.

In 1826 Paul Garnier distinguished himself by showing to the Académie des Sciences in Paris (founded in 1666) a remontoire escapement for clocks, which, because of its coup-perdu nature, allowed seconds to be shown from a half-seconds pendulum. He followed this up in the 1827 Paris Exhibition with a very complicated mantel regulator having the same escapement but in addition offering a number of astronomical indications. This clock almost certainly owed at least something to the influence of Antide Janvier, whose free horological School P.G. is known to have attended after he came to Paris. At all events, Garnier was not long in coming to Janvier’s notice. The latter was happy to teach so promising a pupil, allowing him in 1827 to adopt the style “Elève de Janvier”, despite the fact that P.G. had never worked directly for him.

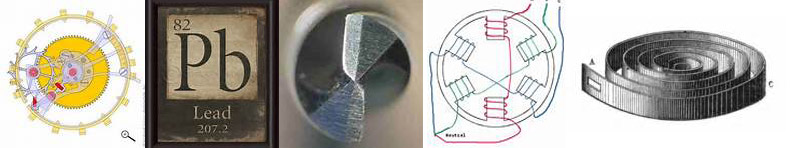

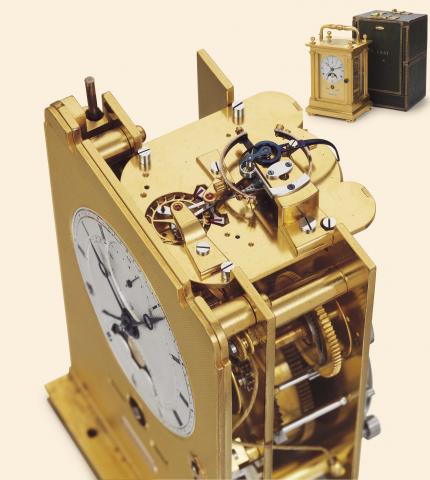

Christopher explained and showed close-up photographs of Garnier’s chaff-cutter escapement, which consists of two parallel wheels mounted on the same pinion. Each tooth of the wheels ending with an inclined surface is opposite to the space of the other. These wheels are bisected by a ruby sector with a radiused edge oscillating from one tooth to another. The tips are at frictional rest on top of the sector and impulse is given to a balance via the inclined plane of the tooth, to the radius edge of the sector. His escapement differed from the cylinder escapement in that it had no lateral pressure on the balance pivots, thus reducing wear and maintaining good balance amplitude. The chaff-cutter proved both practical and un-temperamental. Better still, it could be made largely without hand-work. It was one of the factors in the great success of his carriage clocks; these were exceedingly well made down to the smallest detail, the majority of balances being brass and rectangular in section with radiused edges, the springs flat volutes of six or seven turns. They were, of course, closely related to the best Pendules de Paris, having excellent wheelwork and fine hard pivots and with the added refinement of rack striking-work. Their ‘one-piece’ cases were not only very strong, but were totally free from “rattles” and almost entirely dust-proof.

Numbered pieces to just before no. 180 are not carriage clocks at all but pendules portatives in wooden or cast-brass cases or else with naked movements on wooden bases under glass shades. Their Pendule Paris movements were probably “bought in” from Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont and their escapements changed or added in Garnier’s work rooms. Christopher showed us no. 34 which was primarily an ‘advertisement clock’ made for exhibition purposes to show off its balance-controlled escapement to potential customers. Another, no. 14, a twin of the previous one, is the earliest Christopher has seen or recorded, and it is of particular interest as having a ‘magnifying bubble’ in the top of its glass shade. Almost all pendules portatives and carriage clocks with Garnier’s escapement appear to have been stamped ‘P.G. Breveté’ (P.G. Patent) on the backplate. In No. 14 however, the balance cock is stamped simply ‘Breveté’. His chaff-cutter two-plane escapement has the great advantage of turning the going train through 90 degrees without the need for a contrate wheel, a frequent source of trouble in conventional carriage clocks, mainly because the escape pinions of their original (or replaced) platforms do not match their contrate wheels.

Christopher is currently trying to track down an early example of Garnier’s work Clock No 179, of which only photographs are known. This clock is significant as the escapement seems to be transitional and there is tantalising evidence of a date code on the clock. This clock also has the day and date rollers, (à rouleaux).

Apart from this clock and the series (0) clocks, all clocks up to 1850 appear to have or have had chaff-cutters. The movements were always fitted with finger-type stop work to the going side and sometimes on the striking side. The series (0) clocks (six are known) used a removable platform assembly which consist of the balance cock and bottom potence complete with balance, spring, index, staff and disc only; the escape wheels remaining in the movement. Garnier clocks up to at least no. 1167 wind from the front. Most of the portative dials are engine turned in circular waves. In carriage clocks the dials are engine turned with wavy vertical or horizontal stripes the centres being of a radial (rose engine) pattern. All of these would have been finished with dead silvering, (see Claude Saunier’s ‘The Watchmaker’s Handbook’ for the recipe).The series (0) are timepiece movements, have gold balances, watch type quarter repeating and are reminiscent of Breguet’s work.

The series (1) are both large and small offering various types of complication from alarm work to striking, striking hours and quarters and repeating. Christopher showed us a selection of these. As the series (1) progressed so did Garnier’s popularity, signing himself on a few clocks “Paul Garnier Elève de Janvier”. Later Garnier had clocks signed for various retailers in Europe whom he supplied. Christopher showing us one example, no. 568, a grande sonnerie clock and the first known to be signed “Her. Du Roi” which had an enamel dial set behind a gilt mask, two sector quadrants for sonnerie/silence and for quarts/heures et quarts as well as, unusually, the bells mounted horizontally on the underside of the case.

By 1839 he was entitled to sign himself “Hger. Du Roi” but most likely did not so until after the revolution of 1848. From the numbering and signed mainsprings it is deduced that from 1831 to 1834 Garnier made about 500 clocks approximately a further 350 by 1836 and a further 2000 by 1848. He also signed himself “Her. de la Marine”, probably after 1848.

Christopher also showed us an unusual day date clock employing concentric discs. The clock strikes hours and the half hours, then repeating the same on a gong. This is signed for the retailer ‘Milleret et Tissot à Geneve’ and the striking is achieved by two pin wheels both inwardly facing; a pause is created in the hour to half hour striking as the hammer arbour is shunted, the tail picking up the relative blows from one or other of the wheels in turn. This clock we were told was discovered in pieces covered in verdigris in three boxes at the back of a London clockshop. Obviously a headache for the repairer! Christopher was grateful for the talents of Ian Ford in restoring this and getting it together again.

A feature of Paul Garnier quarter striking work was his use of shunts Christopher illustrated this with the photographs of no 1103, its dial removed to show the two racks and the way the hammers are pushed across to strike the hours and then the quarters. Smaller series (1) have no repeating work and there is only one known example with alarm work; otherwise all are plain striking movements. The cases of this series were uniform in construction the collets to the wheel work the same and always the same gear count giving a 15120 vibration per hour. Jewelling was limited to the balance and its pivots only and should be viewed with suspicion if otherwise. Wooden blocks were fitted to the bases as a practical means to stop the clocks from toppling over if overhanging a ledge, these being numbered the same as the clock but with a further two numbers in ink – the assembler’s works number, perhaps?

The Series (2) clocks were more decorative. Later cases were engraved the dials being enamel with blue black or gold numerals. These movements wound and set from the back which meant that the hand styles could change as they no longer required to be so robust Series (2) (3) and (4) do tend to overlap one another and (3) can be distinguished by the movements not being housed in the one piece style cases but often in a multi-piece case; the movements are the same quality as the series (2) and are mainly repeating. The series (4) however are simpler and mainly have a count wheel striking movement, therefore are not repeating; although some have rack striking and are repeating. The early portatives were also count wheel and could easily be put right if the time shown became out of synch. with the hours struck but the series (4) clocks had one other difference as the rear opening doors of the Series (2) and (3) were replaced with an engraved panel through which the clock was wound.

Christopher is aware of special case designs and two large musical series (1) clocks but said these were disappointing as the musical movements are not in his opinion of good quality. By 1839 Garnier was pursuing other different mechanical interests notably medicine, steam and electricity and his interest in the carriage clocks was waning. Apart from constructing his own clockmaking machines he developed an engine counter for railway and marine use and Christopher’s last photographs were of this, both front and rear, showing how it was connected to a round-ébauche movement.

Garnier also produced electric master and slave clocks to the railway system of France, Gare de Lyon being one of the closest to us that was still using these timepieces until about 20 years ago. Garnier was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur for his work. It is thought that his son continued the retail side of the business after his father’s death.

Christopher concluded his talk by thanking us for our attention and to Charles Allix for firing his enthusiasm all those years ago. After a quick question and answer session Philip Whyte offered our vote of thanks to Christopher for a very interesting evening full of many facts about this fascinating technician; far more than it is possible to convey on this short report.

Duncan Greig.

Following one of our visits last year, to a private collection of clocks music boxes and cars, Ted has offered to give us a guided tour of his collection at “The Victorian Music Room” later this year. Ted will discuss methods of restoration and repair and is happy to answer any technical questions we may have.

Following one of our visits last year, to a private collection of clocks music boxes and cars, Ted has offered to give us a guided tour of his collection at “The Victorian Music Room” later this year. Ted will discuss methods of restoration and repair and is happy to answer any technical questions we may have.